This article was originally published on Health Cents blog on Philly.com. Read the original article.

How bad is opioid misuse? Most of us think it’s really bad

As overdose deaths soar, the opioid epidemic has captured the attention of the White House, Congress, and the public. In a recent survey, about 44% of people say that they personally know someone who has been addicted to prescription painkillers. Increasingly, we see addiction as a health problem rather than as a problem to be solved by the criminal justice system.

As opioid misuse and its treatment enter mainstream health care, it starts to compete for resources with other health conditions. Given the extent of the problem, the pressing question is whether we should now re-prioritize these resources—our attention, our efforts at prevention, and our funding for treatment?

An important first step is to understand just how “bad” each condition is, and how much better it could be with treatment. We health economists have spent years refining the methods to measure how society values prevention and treatment in order to clearly define what is most important to us. And we recently did this for opioid misuse and its treatment. We can now say that it is bad, very bad, for individuals who misuse these substances, and for their families, compared to other conditions.

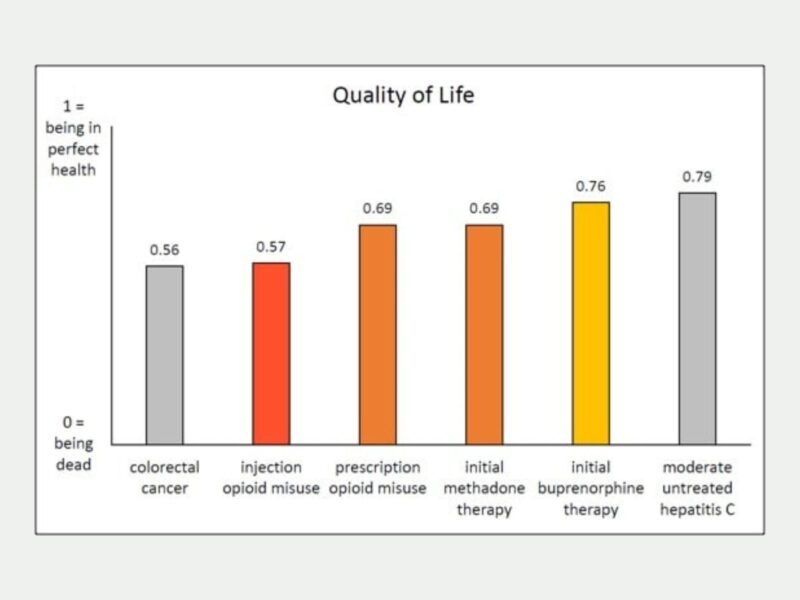

How bad is it? We described life for those who misuse opioids and for those in treatment using short vignettes, and asked a representative sample of the US population to “grade” the quality of that life—from 0 (worst, like being dead) to 1 (best, perfect health).

What we found was startling—on average, the US public thinks that injecting illicit opioids sits at a 0.57 on this scale, which is about the same as how the public graded having colorectal cancer in previous surveys. Misusing prescription opioids was rated somewhat higher at 0.69, but still lower that having moderate untreated hepatitis C, which was graded at 0.79 in similar surveys. We found that spouses suffer as well, with quality of life graded at 0.74 to 0.79 for spouses of opioid misusers, which is about as bad a grade as for having a husband or wife with depression or Alzheimer’s disease.

We didn’t ask about other family members, but it is reasonable to assume that quality of life is perceived as bad for them as well. The public thought that quality of life improved for opioid misusers and their families from medication-based treatment, but the grade depended on type of treatment (methadone was worse than buprenorphine) and stage of treatment (initiation was worse than stable treatment).

Importantly, this is what the US public thinks about how bad it is. We did not measure how bad the user thinks it is, when actively misusing or when in treatment. But what the public thinks is critically important—it guides our attention and our resources. Just as in cancer—our perceptions of the disease guides our investment in prevention and treatment.

Even though people with cancer cope far better than we all expect, our collective perceptions influence policy, as they should for opioids as well. We found that the experience of opioid misuse is considered as bad as some cancers, and worse than problems we spend considerable resources on. For families, opioid misuse is as bad as other significant health conditions.

As Congress, the Administration, and state leaders consider new ways to address the opioid crisis, we urge policymakers to consider the far reaching effects of this disease for all who are affected—individuals, families, and communities, and how it compares to other diseases that have our attention and resources.