We’re barely using a key resource to help people with addiction

This op-ed originally appeared in KevinMD.

Rachel was making her 25th visit to the emergency department. The wound on her leg from injecting drugs had spread to her entire calf and required a lengthy course of antibiotic treatment in the hospital. The few times she had been admitted to the hospital, she had left without finishing treatment because the pain and withdrawal symptoms were too much to bear. On her most recent visit, she finally stayed to complete the treatment. She was then connected to an outpatient program to receive medication for her addiction, where she met Tara.

Tara introduced herself to Rachel as someone who once used drugs and now helps people like Rachel get back on their feet. In the following months, Rachel agreed to participate in a research study to receive support from Tara and a social worker.

Tara checked on Rachel at least weekly. Rachel was too ashamed of her chaotic life to let her family know her whereabouts. At Tara’s encouragement, she left the street and went back to her family. When Tara found out that Rachel’s family was spending hundreds of dollars each month ordering wound care supplies from Amazon, she worked with Rachel’s doctor to send Rachel supplies fully covered by Medicaid. Tara helped Rachel re-enroll in Medicaid, apply for food stamps, and get a mailing address at a local program serving people who are homeless and use drugs. They talked about how Rachel might find purpose after a decade full of shame and trauma. Rachel is now thinking of going back to school.

The last time they talked, Tara told Rachel that the study that had funded Tara’s work for four years was ending. The medical center had yet to find the money to continue the program that had supported Rachel so well.

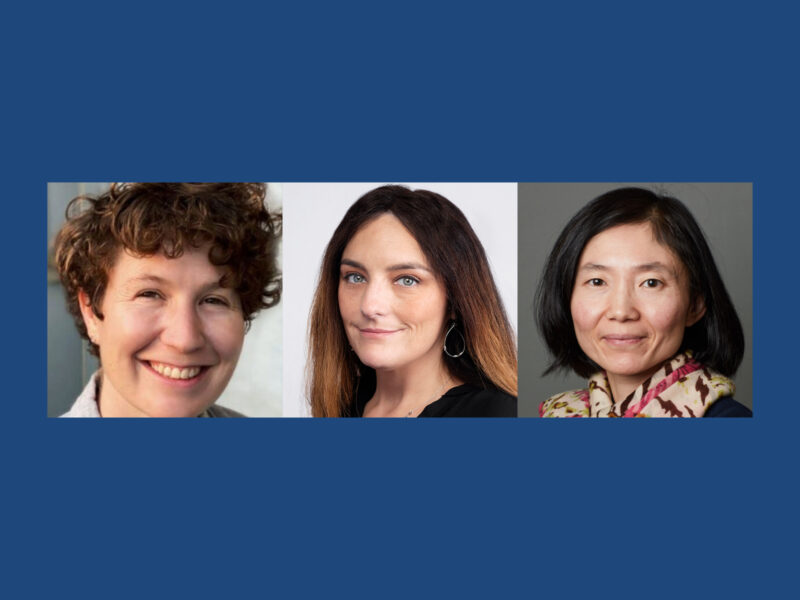

We are a health policy researcher, a provider with lived experience, and a physician caring for patients with addiction. We are all too familiar with how the American health care system strains to tackle the opioid crisis yet barely makes use of professionals like Tara who know the disease intimately.

In the U.S., the opioid crisis claimed more than 81,000 lives last year. An estimated 2.7 million individuals struggle with opioid use disorder, a chronic condition with huge human and societal tolls. The struggle is so difficult, and the associated stigma so deeply entrenched, that care delivered by traditional providers, like doctors, nurses, and mental health clinicians, is not enough.

Professionals like Tara are known as “peer recovery specialists” or more simply, “peers.” Peers are living testimonies that recovery is possible. All 41 states that cover peer services through Medicaid require peers to be trained, certified, and supervised. Peers spend a lot of time with patients, but also in texting, calling, and working with the patient’s doctors, and finding patients community resources.

Research studies have shown promising but inconclusive evidence on the effectiveness of peers in helping people like Rachel. Peer programs vary considerably in how peers are trained, what activities they engage in, and where and with whom they work. Such variation adds to the difficulty of generating definitive research evidence. However, waiting for research data to coalesce before deploying a promising approach is a luxury that we do not have in this raging crisis.

Continue reading the story at KevinMD, published on December 14, 2024.

The study referenced in this op-ed, “Medicaid-Covered Peer Support Services Used by Enrollees With Opioid Use Disorder,” was published in JAMA Network Open on July 9, 2024.