Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder Lowers Overdose Risk in Commercially Insured Individuals

This post also appeared on the University of Pennsylvania Leonard Davis Institute Health Police$ense blog.

“Medications for opioid use disorder saves lives.”

That’s the title and conclusion of a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, based on a review of the scientific evidence. In a new study in Drug and Alcohol Dependence, CHERISH investigators Jake Morgan, Bruce Schackman and Benjamin Linas add to this evidence base by examining the real-world effectiveness of medications in preventing overdoses once treatment for opioid use disorder has begun.

Using a database of commercially insured individuals, CHERISH investigators examined overdose risk on and off treatment with three federally approved medications for opioid use disorders–buprenorphine, extended-release injectable naltrexone, and oral naltrexone. (Methadone was excluded because it is not reliably reported in commercial claims.) From 2010-2016, they identified nearly 47,000 individuals diagnosed with an opioid use disorder and prescribed medication with an average follow up of 1.5 years per person. During that time, 1,805 individuals experienced 2,755 opioid-related overdoses (both fatal and non-fatal) as indicated by ICD-9 and ICD-10 inpatient and outpatient codes. The authors used pharmacy claims to determine whether an individual was on or off treatment in a given week.

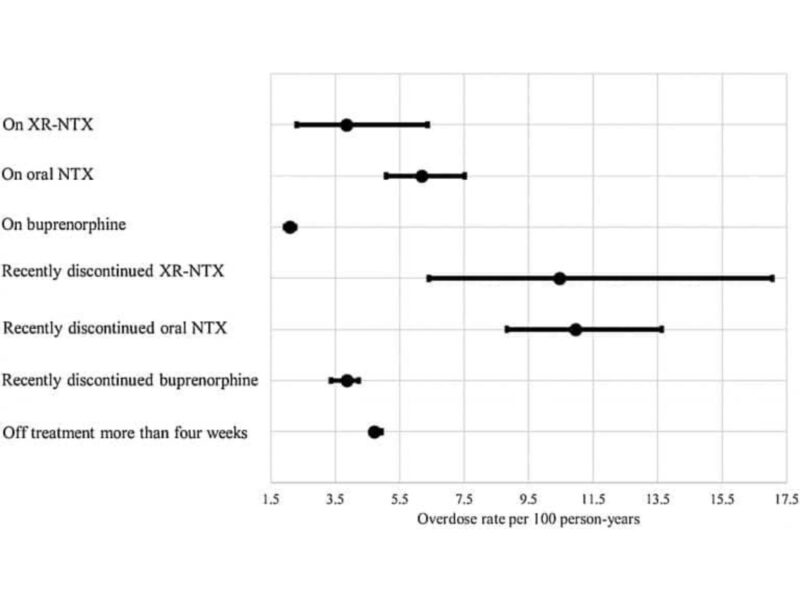

Most overdoses (2,020) occurred while individuals were not on treatment, resulting in a rate of 4.98 overdoses per 100 person years (PY). Individuals currently on buprenorphine experienced fewer overdoses (2.08 overdoses/ 100 PY) than those on injectable naltrexone (3.85 overdoses/ 100 PY) or oral naltrexone (6.18 overdoses/ 100 PY). After controlling for other factors such as age, sex, region of residence, insurance coverage, polypharmacy prescriptions, and visits to a treatment facility, individuals receiving buprenorphine were 60% less likely to overdose in a given week than individuals not on treatment. The overdose risk for those on naltrexone was not significantly different from those not on treatment.

To assess the risk of a “rebound” overdose after treatment was discontinued, CHERISH investigators looked at overdoses within a four-week window after discontinuation. They did not find a higher risk of overdose within four weeks after discontinuation of either buprenorphine or naltrexone. The relatively small sample of individuals on oral and injectable naltrexone made estimating the associations between overdose and naltrexone treatment and discontinuation challenging, but the lack of clear evidence of a protective effect of naltrexone is useful information for patients and prescribers.

The authors found that risk of overdose was associated with multiple prescribed drugs and a concurrent diagnosis for another substance use disorder such as alcohol, cannabis, cocaine and sedatives. They also found geographic variation in overdose risk, with patients in the Northeast and Midwest experiencing a higher risk of overdose. Being a child or dependent of a primary beneficiary was also associated with a higher risk of overdose, after controlling for age, and suggests there may be a group of emerging adults at high risk who will age out of parental insurance coverage.

The findings suggest that buprenorphine reduces overdose risk and supports the expansion of medication treatment for opioid use disorder. In 2017, about 47,000 people died from opioid-related overdoses. Less than 20% of those with an opioid use disorder receive treatment, and even fewer receive medication treatment. Increased access and use of evidence-based medications is critical to addressing the opioid overdose epidemic. Further research is needed to improve our understanding of the risks and benefits unique to each treatment in order to better tailor treatment to individual patient needs.